Why do I have such a large distance matrix

One of the more common questions we get on the mothur forum and to the mothur.bugs email list is some variant of, “My distance matrix takes up 100 GB and it won’t go through cluster or cluster.split to make OTUs. What can I do?” Having answered some variant of this question 1000 times, I fear that I might stroke out if I answer it a 1001st time. So, allow me to explain what’s going on, what you should have done, what you can do, what you should do, and why you should care. I’ll try not to rant… to much.

What’s going on?

Without telling me how your data were generated, let me guess… Your PI got greedy. She heard Illumina can now generate paired 300 bp reads and so it would be reasonable to sequence the V1-V3 region or some other region than the V4 region. In this design your paired reads overlap just a smidge. Another common variant of this is that you have paired 250 bp reads and you went after the V4-V5 or V3-V4 region or that you used a HiSeq to sequence the V4 region with paired 150 bp reads. Sound familiar? Read on.

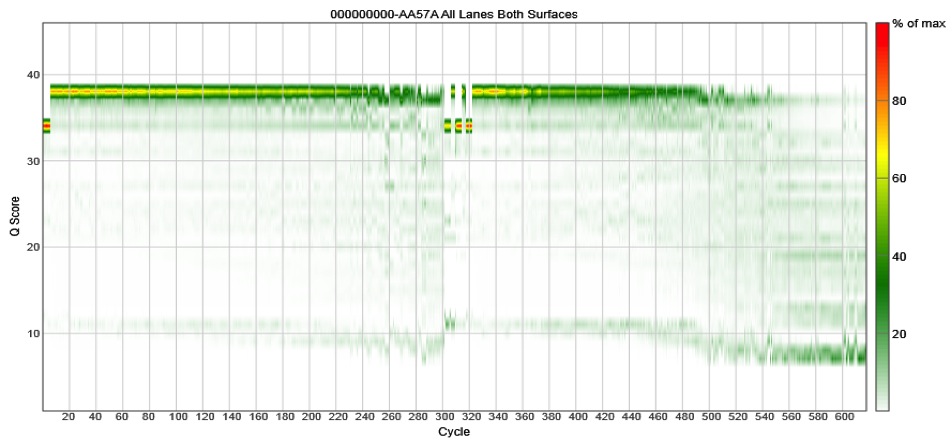

The problem is that if the reads do not fully overlap, your assembled reads (i.e. the contigs) will have a high error rate. Don’t believe me? Take a look at our 2013 paper using the V2 MiSeq chemistry where we saw that the reads must fully overlap to get good desnoising of the data. If they don’t fully overlap, the error rates escalate. This is independent of cluster density or percent PhiX. We’ve gone back and done the newer V3 chemistry and found that the data quality craps out around cycle 500. Again, this is independent of cluster density or percent PhiX. Check these data out for the V4-V5 region, which is 375 bp fragment:

[ In essence, Illumina took the old boxes of 500 PE V2 kits, and scratched out the 5 and 2 and replaced them with a 6 and a 3. I have shown Illumina these data and they ask, “what’s your point?” ]

To take a step back, if you look through our MiSeq SOP, you’ll see that we go to great pains to only work with the unique sequences to limit the number of sequences we have to align, screen for chimeras, classify, etc. We all know that 20 million reads will never make it through the pipeline without setting your computer on fire. Returning to the question at hand, you can imagine that if the reads do not fully overlap then any error in the 5’ end of the first read will be uncorrected by the 3’ end of the second read. If we assume for now that the errors are random, then every error will generate a new unique sequence. Granted, this happens less than 1% of the time, but multiply that by 20 million reads at whatever length you choose and you’ve got a big number. Viola, a bunch of unique reads and a ginormous distance matrix.

What should I have done?

Ahem. Since I’d rather not leave this section with a one word answer, allow me to rant for 100 words. There has been a flury of papers in the recent literature with titles like, “An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform.”. If you go old fashion and actually read the paper you’ll find the glaring omission of error rates or any indication of how it’s actually better than previous methods. I’m picking on this paper because it’s title is just obnoxious and wrong, but there are numerous other examples in the literature. So your PI sees the title, sends it to you and says, do this - it’s improved! Or you have a sequencing core on campus and they want to develop their own 16S rRNA gene sequencing pipeline, but they don’t know to care about error rates. So you’re stuck with bad data. To quote a recent emailer, “My PI tells me that he paid for this data and it’s my job to make it work.” Nice guy.

What you can do?

Bioinformatically, you can always use the phylotype-based approach where you just classify everything and then analyze the bins based on classification. Classification does not seem to be super sensitive to error rates. But the problems with phylotypes are numerous including the fact that all databases are lousy, the names have questionable meaning, and they don’t give you the resolution of a 3% distance cutoff. You can also try to just shove the data through cluster.split and use taxlevel=6 as the level that you split on. Usually there’s one genus that holds most of the sequences and so this really doesn’t help much. You’re probably thinking you’d like to try the large=T option in cluster.split. Don’t bother, it will actually suck up more RAM and take longer to run.

What you should do?

In our lab it costs about $5000 to sequence 400 samples on a MiSeq using our protocol. How much is your time worth to you? How much is that extra RAM you’re thinking about buying? How much does time on your university’s superduper computer cost? But really, how much is good data woth to you? I suspect the sum of those questions is more than $5000. What should you do? Resequence the data and do it right. If you can’t find someone to do it right, let me know and I can hook you up with people that can.

Why you should care?

I personally find it comical that there is a need to justify having good data. Think about that. Go to your PI and ask them why they think you should submit a paper that uses data wiht a 10-fold higher error rate than the best method out there. Let me know what they say. I’ll wait… Ok, before you go to your PI, here’s some ammunition. What are the effects of using low quality sequence data?

- Inflated number of OTUs and diversity

- Increased distance between samples

- Increased difficulty in indentifying chimeras

- A grimy feeling that makes you want to take a bath

Conclusion

The root of the original question is a common problem within in the world of so-called next generation sequencing. The ability to generate methods and use the ability to generate data with the method is often seen as the only type of validation one needs to publish. If you are going to propose a method or a pipeline, it’s got to have error rates or some other objective metric to say it’s better and how much it’s better. Otherwise, you’re just padding your resume and being stubborn.